Necrotic Enteritis

Necrotic Enteritis

Necrotic Enteritis (NE) is the most common and financially devastating bacterial disease in modern broiler flocks. Early signs of an NE outbreak are often wet litter and diarrhoea, and an increase in mortality, that may not be significant. However, the depression of growth rate and feed efficiency of birds become noticeable by day 35 due to intestinal damage and the subsequent reduction in digestion and absorption of food. Subclinical infections are more economically damaging due to these factors. Furthermore, increased condemnations at processing due to liver lesions associated with subclinical NE can occur. The severity of clinical signs varies with the age of the birds.

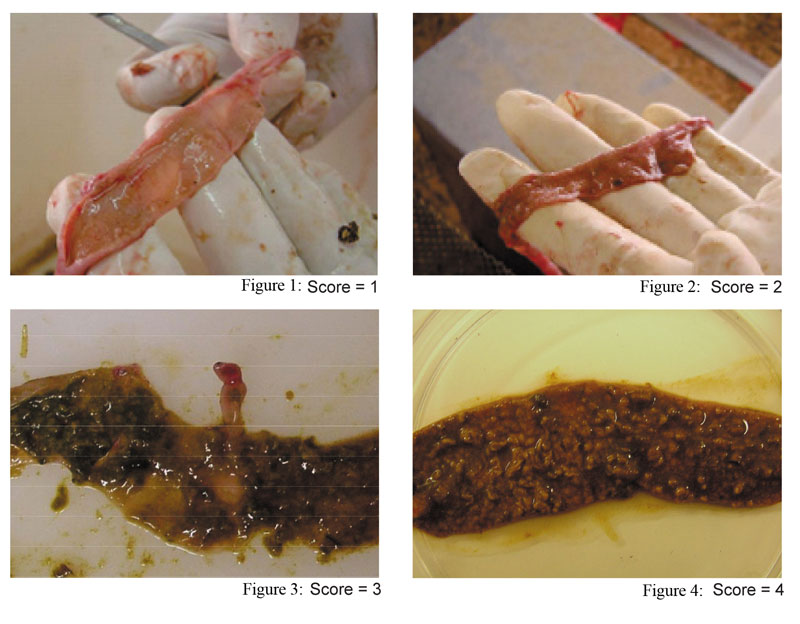

Necrotic enteritis lesion scores (1-4)

NE is a complex, multifactorial disease with many unknown factors that influence its occurrence and the severity of outbreaks. In particular, sporadic outbreaks of NE can occur frequently in farms where antibiotics are not used as growth promoters, coccidial infections are not controlled, the husbandry practice is not strict, and diets based on viscous grains with animal protein sources.

Predisposing factors for the rapid proliferation of C. perfringens and the onset of NE include other dietary and husbandry factors such as damage to the intestinal mucosa through coccidial infection or a change in the normal intestinal microflora as a result of a change in diet formulation, such as the inclusion of a high level of viscous cereal grains and/or animal by-products like fish and meat meal.

What causes Necrotic Enteritis?

It is an infectious disease caused by Clostridium perfringens, which is a gram-positive, anaerobic bacterium that can be found in soil, litter, dust and at low levels in the intestine of healthy birds. Clostridium perfringens only causes NE when it transforms from non-toxin producing type to toxin producing type. There are five types of C. perfringens (A, B, C, D and E) which produce a number of toxins (alpha, beta, epsilon, iota and CPE). The α-toxin, an enzyme (phospholipase C), is believed to be a key to the occurrence of NE. However, a recent study has shown that an isolate that does not produce α-toxin can still cause disease and additionally, a new toxin called NetB has been recently been identified in disease causing C. perfringens isolates.

Prevention and treatment of Necrotic Enteritis

Poultry CRC Deputy CEO, Vivien Kite; Monash University PhD student, Anthony Keyburn; and Poultry CRC Chairman, Jeff Fairbrother at the Cooperative Research Centres Association (CRCA) Conference in Perth (May 2007)

Outbreaks of NE can be effectively prevented by including antibiotics such as bacitracin and avilamycin in the feed. In addition, effective control of coccidial infections can greatly reduce the risk of NE outbreaks. Furthermore, if antibiotics are not used in the feed, strict on-farm hygiene management practice, good climate control of the buildings and careful selection of feed ingredients for diet formulation are all important in maintaining production efficiency. In the Nordic countries, where antibiotics have been removed from the feed, ionophorous anticoccidials have been used to manage NE.

Following the ground-breaking discovery that alpha-toxin is not the main causative factor for NE, by a Monash University PhD student funded by the Poultry CRC, Anthony Keyburn, CSIRO Livestock Industries researchers have patented NetB, the toxin they believe is the causative agent. The research team has identified the novel toxin and is now working on how it might be used to create the first truly effective vaccines against NE.

Further information

- Choct, M. (2005). Australian Poultry CRC Fact Sheet: Necrotic Enteritis.

- Keyburn AL, Sheedy SA, Ford ME, Williamson MM, Awad MM, Rood JI, Moore RJ. Alpha-toxin of Clostridium perfringens is not an essential virulence factor in necrotic enteritis in chickens. Infect Immun. 2006 Nov;74(11):6496-500. Epub 2006 Aug 21.

- Keyburn AL, Boyce JD, Vaz P, Bannam TL, Ford ME, Parker D, Di Rubbo A, Rood JI, Moore RJ. NetB, a new toxin that is associated with avian necrotic enteritis caused by Clostridium perfringens. PLoS Pathog. 2008 Feb 8;4(2):e26.

- Branton, S. L., Reece, F. N. & Hagler Jr, W. M. (1987). “Influence of a wheat diet on mortality of broiler chickens associated with necrotic enteritis.” Poultry Science 66, 1326–1330.

- Hofacre, C. L., Froyman, R., Gautrias, B., George, B., Goodwin, M. A. & Brown, J. (1998). “Use of Aviguard and other intestinal bioproducts in experimental Clostridium perfringens-associated necrotizing enteritis in broiler chickens.” Avian Diseases 42, 579–584.

- Kaldhusdal, M. & Løvland, A. (2000). “The economical impact of Clostridium perfringens is greater than anticipated.” World Poultry 16, 50–51.

- Kaldhusdal, M. & Skjerve, E. (1996). “Association between cereal contents in the diet and the incidence of necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens in Norway.” Preventive Veterinary Medicine 28, 1–16.

- Parish, W. E. (1961). “Necrotic enteritis in the fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus). I. Histopathology of the disease and isolation of the strain Clostridium welchii.” Journal of Comparative Pathology 71, 377–393.

- Riddell, C. & Kong, X. M. (1992). “The influence of diet on necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens.” Avian Diseases 36, 499–503.

- Truscott, R. B. & Al-Sheikhly, F. (1977). “Reproduction and treatment of necrotic enteritis in broilers.” American Journal of Veterinary Research 38, 857–861.

- van der Sluis, W. (2000a). “Necrotic enteritis (1): Clostridial enteritis a syndrome emerging worldwide.” World Poultry 16, 56–57.

- van der Sluis, W. (2000b). “Necrotic enteritis (3): Clostridial enteritis is an often underestimated problem.” World Poultry 16, 42–43.