Flies

Flies

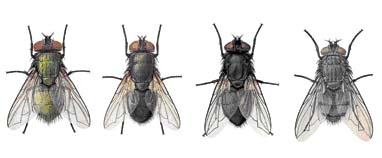

There are many species of flies that tend to congregate around poultry facilities. The main species found in Australia include the house fly (Musca domestica), the little house fly (Fannia canicularis), the false stable fly (Muscina stabulans) and blow flies (Calliphoridae sp.).

The main factors affecting fly types and numbers on a poultry farm include geographic location, season, current seasonal conditions, proximity and density of other favourable fly breeding areas and management of the poultry farm.

Accumulated poultry manure or litter, moist spilt feed and decaying organic matter such as uncovered carcases or broken eggs will increase fly populations.

Major fly species

The House Fly (Musca domestica)

The House Fly

The house fly is 6 to 7 mm long, with the female usually larger than the male. The eyes are reddish. The thorax has four narrow black stripes. The abdomen is gray or yellowish with a dark midline and irregular dark markings on the sides. The underside of the male is yellowish. The sexes can be readily separated by noting the space between the eyes, which in females is almost twice as broad as in males. The life cycle can be as short as seven days under ideal conditions. Each female produces up to 200 eggs which are laid in six or more batches at three- to four-day intervals. Maggots hatch in 12 to 24 hours and complete their development in four to seven days. Mature maggots are 3 to 9 mm long, creamy white and cylindrical. They form into pupae which are dark brown and 8 mm long and from which adult flies emerge in three to four days. Adult flies live an average of three to four weeks.

The Little House Fly (Fannia canicularis)

The Little House Fly

The little house fly is about 5–6 mm long. The adult is blackish-grey with three indistinct black dorsal longitudinal stripes. The sides of the thorax are a lighter colour; the legs are black. The head is grey with black frontal stripes and grey sides. Like the house fly, the male eyes are nearly together, while the female eyes are further apart. The complete lifecycle ranges from 18 to 22 days but may be longer depending upon temperature. Female flies begin laying eggs two to five days after emerging. Maggots are brownish red, flattened and spiny and hatch in 36 to 48 hours. These maggots feed and develop for seven to 10 days. Within nine to 14 days, a new generation of flies emerges. Adults may live as long as two months.

The False Stable Fly (Muscina stabulans)

The False Stable Fly

The false stable fly is larger and more robust than the house fly. Overall colour is dark grey, with the head a lighter whitish-grey. The grey thorax has four longitudinal stripes and the posterior tip of the scutellum (dorsal rear lobe of the thorax) is pale yellow. The abdomen is grey and black with a blotched appearance. The legs of the false stable fly are partly red-gold or cinnamon. The life cycle is about two weeks in temperate summer conditions but can take five to six weeks. Adult females lay 140 to 200 eggs. Larvae require 15 to 25 days to mature and resemble those of the house fly. Several generations are produced each summer.

Blow flies (Calliphoridae species)

Blow Flies

Blow flies are robust, with a metallic sheen to the body, and are variously coloured: bright green, blue, bronze-black or copper. Body length is 8 mm. The thorax has no stripes and there are stout bristles on both sides of their thorax and abdomen tip. The life cycle usually requires between 10 to 25 days. Female blow flies commence laying eggs one week after emerging from the soil and live for two to eight weeks. Eggs are laid in masses ranging from 40 to 1000, although the larger masses are usually the result of egg-laying by several females at the same location. Incubation may last four to 4.5 days, but hatching usually occurs in less than 24 hours when conditions are warm and humid. Maggots usually complete development in four to 10 days. At the end of this period, larvae typically burrow in the upper centimetres of the soil and pupate for up to a week. Adult flies emerge and make their way to the soil surface. They usually complete four to eight generations each year.

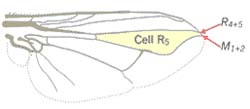

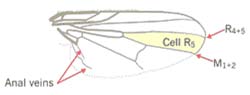

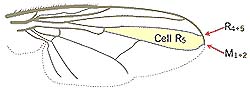

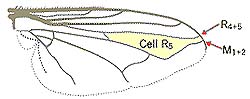

Identification Using Wing Venation

One of the tools that entomologists use to differentiate between fly species is to compare veins on the wings. Wing venation (the pattern made by the veins) varies between species.

Effects on poultry production

None of these flies are biting flies and they are a problem for poultry principally through annoyance, which can affect stress levels and consequently productivity, and the potential for spread of disease. Blow flies can also infest and worsen wounds, possibly leading to septicaemia (blood poisoning). Excessive fly numbers can lead to increased downgrading of shell eggs, due to soiling of the shells by flies, and can result in complaints from neighbours.

Fly control methods

Detailed discussions of fly control measures can be found at The Purdue University website.

Further information

- Poultry Health Handbook 4th Ed, 1994. L. D. Schwartz, Pennsylvania State University.